Assessing Lisfranc Injuries

This post will spotlight an article I found eye opening in assessing Lisfranc injury, “Sonographic Evaluation of Ligament Injuries.”1 The article describes a remarkably easy and quick ultrasound assessment of the ligament in the clinical setting. Part of my presentation at the recent KSCPM Annual Spring Conference in Orlando in February, this article is fully responsible for my incorporating an assessment of the Lisfranc ligament as part of my standard ultrasound protocol following foot and ankle injury.

Lisfranc injuries, as we know, can be difficult to diagnose. They are often missed (20% missed diagnosis rate) and have a frequency of 1:50,000 in foot injuries.2 The patient will present with a history of injury, and pain and swelling that is exacerbated with activity and located at the level of the midfoot. Unless there is a fracture or diastasis present, X-rays will be negative. Standard views, and if possible, weight-bearing views should be taken with the foot abducted 15 degrees in the DP. This position stresses the Lisfranc. If there is instability due to the injury, it is more likely to be picked up in this position. MRI is the gold standard, with 94% specificity, 89% sensitivity, and a 74% diagnosis rate.3

I believe diagnostic ultrasound is clinically useful for any structure if three criteria are met: 1) the structure can be imaged, 2) the structure is easily imaged and there is little chance of operator error, and 3) ultrasound can be performed efficiently in the office. As we shall see, all three criteria are met in assessing the Lisfranc ligament complex.

- When we think of the Lisfranc ligament, we think of the interosseous ligament. We will not be able to see this on ultrasound. Bone blocks the view and sound waves are blocked by bone. That is true with any structure (i.e., most of the spring ligament), however, you can indirectly assess the ligament be assessing another part of the Lisfranc complex (comprised of the dorsal, interosseous, and plantar ligaments). In this case, the dorsal ligament is a good indicator of the interosseous ligament and the Lisfranc complex as a whole. This dorsal ligament is easily viewed on ultrasound and can be viewed very quickly and reliably.

- The dorsal ligament is easy to image.

- The dorsal ligament can be assessed quickly.

In a previous post, we discussed the factors to consider when optimizing an image. In this case, you need to use the highest frequency your unit is capable of. This structure (the dorsal ligament) is very superficial, so high frequency should be used for the best resolution and the depth should be dialed to 1 cm. The focus (the indicator on the right of the screen that improves the lateral resolution) should be at the level of the structure, in this case, near the top of the screen. These factors are critical in imaging such a small structure. The gain, if needed, should be adjusted while scanning.

The patient should be standing with the foot abducted 15 degrees to stress the ligament. This may not be possible if the patient is in significant pain. Place the probe, with a copious amount of gel, in a transverse orientation on top of the foot (Figure 1). This will represent a coronal scan of the foot. The probe should be at the mid shafts of the first and second metatarsals. From this position, slide the probe proximally. It is vital that the hyperechoic metatarsals are always present in the image. These appear as bright white arcs and the brightness should be crisp and clear (Figure 2). As you slide the probe you will have to readjust to keep the metatarsals in view and clear. This is the time to assess the gain. The cortex of the metatarsals appears as the echogenic bright areas of the metatarsals. Soundwaves will not penetrate bone. The darkness deep to bone is called acoustic shadowing and at the optimum gain, this should be black. If you see echo, the gain is too high. Decrease the gain until it is as dark as it can get, while the metatarsals remain bright white.

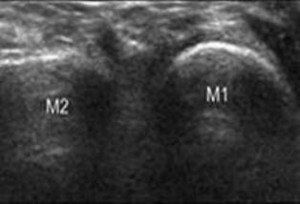

From this position the probe needs to be moved proximally. The first metatarsal will disappear as you encounter the anechoic (black) joint space of the first metatarsal/cuneiform. The second metatarsal will stay visible, since anatomically it projects further proximally. Then, the hyperechoic medial cuneiform will come into view.

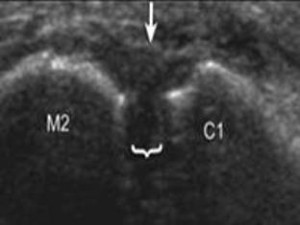

You now have in view the dorsal aspect of the medial cuneiform and the second metatarsal (Figure 3). Connecting these two bones will be the dorsal ligament of the ligament complex. It runs transversely to slightly obliquely to the foot, but will appear in the longitudinal plane of the ultrasound because of the orientation of the probe. Thus, you will be expecting to see hyperechoic (less white than bone but still white) fibrous bands in parallel alignment. You may have to adjust the gain slightly to bring this out more clearly.

The ligament should be parallel and not bulging dorsally. (Figure 4A is normal and 4B is abnormal.) You should be able to make out the fibrous architecture of the ligament. Also, you should be able to see clearly the anechoic (black) space (normally 1 mm) between the medial cuneiform and the second metatarsal (Figures 4A and B). This can easily be measured with digital calipers. A diastasis can be seen and usually the space will be greater than 3 mm (Figure 5). What is really nice about ultrasound is that you can, and should, compare the abnormal side to the normal side.

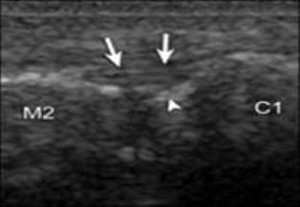

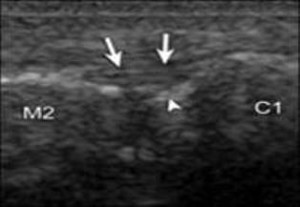

Figure 4A. Arrowhead, bright echo of normal part of the cuneiform, which could be confused with a fracture; arrows, dorsal ligament; C1, medial cuneiform; M2, second metatarsal.

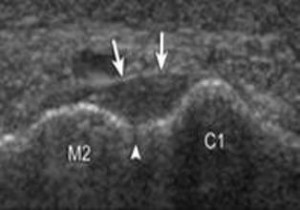

Figure 4B. Arrowhead, normal space of 1 mm; arrows, dorsal ligament; C1, medial cuneiform; M2, second metatarsal.

In summary, if diagnostic ultrasound is one of your clinical assessment tools, this article should be an essential component in your library. It clearly shows that ultrasound can assess the Lisfranc ligament. You may still need an MRI, which is the gold standard, but with ultrasound you can quickly and easily acquire useful information to better treat the patient. This would be an abbreviated exam, coded 76882, if you assessed only the Lisfranc ligament and some other structures. If the exam was part of an ankle survey, which entails imaging all the structures of the ankle, you can code 76881.

References

Suggested Readings

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.